What are the key steps in educational program implementation? This is a question that is regularly asked by educational nonprofits, districts, and schools. because it might be overwhelming to bring a vision to life. However, adoption can be far more successful and long-lasting with a methodical, data-driven, and student-centered strategy.

We examine the essential processes in implementing educational programs in this extensive handbook. by breaking things down into manageable, doable steps. We’ll also examine the significance of each phase, potential difficulties, and ways in which educational leaders may assist their teams at each level.

Why implementation matters as much as design

It’s important to comprehend why implementation frequently fails—not because of a bad idea, but rather because of flaws in planning, communication, or follow-through—before talking about the essential phases in implementing educational programs.

- Objectives are ambiguous or impractical.

- Employees are not motivated or trained.

- There is no measurement or adjustment of progress.

- Resources are not distributed appropriately.

Launching a project is only one aspect of implementation; another is setting up the proper framework to ensure that it becomes ingrained in the educational culture and has a long-lasting effect.

Step 1: Conduct a comprehensive needs assessment

The first response is: What are the essential steps in implementing educational programs? is always based on being aware of where you are starting.

A requirements analysis aids leaders in:

- Determine which particular issues or gaps the program seeks to fill.

- Recognize the background: earlier efforts, staff capacity, cultural issues, and student demographics.

- Collect information using questionnaires, focus groups, classroom observations, and measures of academic achievement.

This stage guarantees that the program reacts to actual, documented needs as opposed to conjecture. Additionally, baseline data is created so that the program’s impact can be later measured.

Participate in this process with a variety of stakeholders, including parents, community members, teachers, and students. This ensures that the program is culturally sensitive and relevant while also fostering trust.

Step 2: Define clear, measurable goals and objectives

Because they seek to “improve student outcomes” without specifying which outcomes, for whom, and by how much, many educational programs fall short.

Goal-setting should always be SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) when attempting to identify the essential steps in the implementation of educational programs. For instance:

- Within two years, raise math performance in the fifth grade by 15%.

- Over three semesters, cut the chronic absenteeism rate among ninth graders by 10%.

Clear goals:

- Make decisions every day.

- Assist in assessing success.

- Share the goal with all parties involved.

They also make it easier to modify plans if data shows goals aren’t being met.

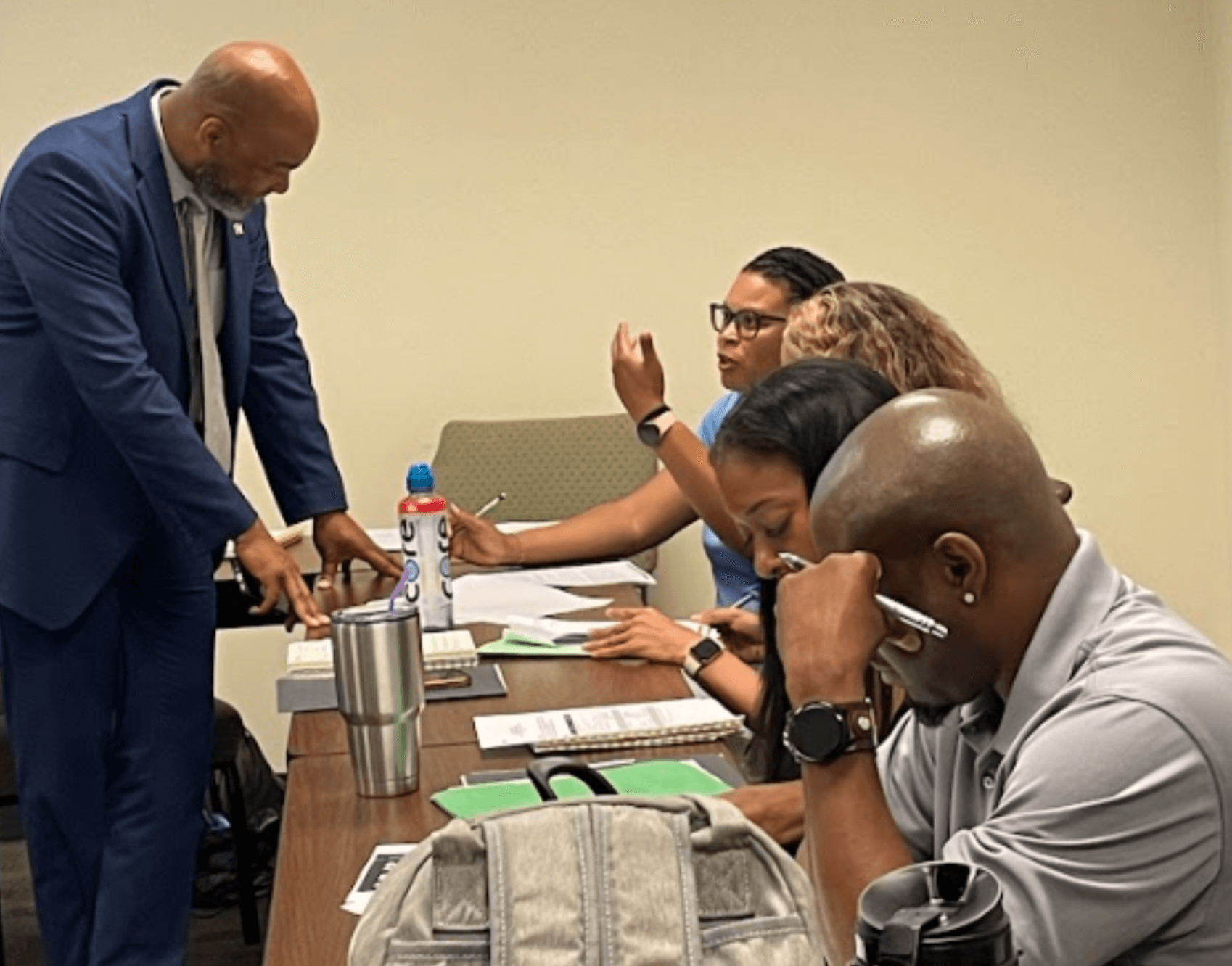

Step 3: Engage and build capacity among stakeholders

One of the most often disregarded responses to the question, “What are the key steps in the implementation of educational programs?” is the involvement of stakeholders.

No program can be successful on its own. Parents, students, teachers, administrators, and support personnel all influence how a project is implemented in real life.

Important steps:

- Explain the program’s goal and justification.

- Provide professional development to employees so they can adopt new procedures with confidence.

- Establish feedback loops so that interested parties can discuss what is working and what needs to be changed.

- To create momentum, acknowledge and celebrate early victories.

People become more committed and less resistant when they feel heard and prepared.

Step 4: Develop a detailed implementation plan

Planning makes a vision a reality. What are the crucial steps in implementing educational programs in the fourth phase? is about creating a well-defined plan.

A solid implementation strategy ought to comprise:

- Timeline: What time will each stage begin?

- Roles: Who has accountability for every action?

- Resources: What kind of money, supplies, or personnel are required?

- Communication plan: How will we provide updates?

- Plans for contingencies: What happens if something goes wrong?

The team may monitor progress, identify bottlenecks early, and maintain team alignment by documenting everything.

Step 5: Pilot the program and collect early data

One of the most important elements in implementing educational programs is piloting before a full-scale rollout.

Why take flight?

- Test hypotheses regarding what functions well and what doesn’t.

- Determine any resource shortages or logistical difficulties.

- Adjust support and professional growth in response to practical input.

- Collect preliminary data in order to promote wider use.

Best practices:

- Select classrooms or pilot locations that represent the variety of your community or district.

- Gather qualitative information (student focus groups, teacher interviews) as well as quantitative information (test results, attendance).

- Keep the pilot period brief enough to allow for quick adjustments yet long enough to yield significant effects.

Step 6: Scale thoughtfully and monitor continuously

Scaling a program involves applying lessons learnt to new situations rather than precisely reproducing what worked in a pilot.

While scaling:

- New hires should continue their professional development, and current employees should receive refresher training.

- Utilize real-time data dashboards to monitor results, fidelity, and participation.

- Organize frequent check-ins to discuss difficulties, celebrate victories, and assess progress.

It shouldn’t feel harsh to monitor. Rather, it should support the team’s growth, learning, and accomplishments.

Step 7: Evaluate impact and sustainability

Lastly, what are the essential measures in implementing educational programs? emphasizes long-term assessment.

This involves:

- Measuring change by comparing data from before and after the program.

- Conducting focus groups and stakeholder surveys to learn about opinions and experiences.

Addressing common challenges

Real-world difficulties still occur even when one is well aware of the crucial procedures involved in implementing educational programs:

Limited time or resources: To spread costs, give high-impact ideas priority and implement them in phases.

Staff turnover: To lessen interruptions, record procedures and create institutional memory.

Shifting priorities: To keep the program current, match it with more general district or state objectives.

Schools can be proactive instead of reactive by foreseeing problems.

Why culture and communication matter

Beyond technical procedures, communication and culture play a role in whether an educational program sticks or disappears.

Important cultural motivators:

- Promoting exploration and failure-based learning.

- Valuing teacher independence while pursuing common objectives.

Communication that works:

- Increases openness and trust.

- Aids in program adaptation as needs evolve.

Real-world example: Literacy initiative in middle school

- Needs assessment: According to data, 40% of seventh graders struggle with reading comprehension.

- Goals: Within two years, raise grade-level proficiency by 20%.

- Engagement: Parents learn how to encourage reading at home, and teachers are trained in new teaching techniques.

- Implementation plan: identifies the texts, resources, and tests that will be used, along with who will use them.

- Pilot: Teachers give input after the program is tested in three schools.

- Scaling: The district-wide launch of the modified curriculum includes continuous coaching.

- Evaluation: Data indicates a 15% improvement; year three techniques are improved.

Final thoughts: Turning plans into impact

Being aware of the crucial phases involved in implementing educational programs. is more than just an intellectual exercise; it’s a path to tangible, quantifiable life improvement for kids.

What are the key steps in educational program implementation? Educational leaders may develop good ideas into revolutionary programs by combining data, clear goals, stakeholder participation, careful planning, and continuous evaluation.

Effective implementation is a continuous process of introspection, adaptation, and cooperation rather than a one-time occurrence. However, by taking these actions, the path becomes more obvious and the goal—better educational results—becomes more reachable.