Budget Analysis and Financial Strategy for Miami Dade County Public Schools

In 2024, EduSolve, LLC partnered with Partnerships for Miami to conduct a comprehensive budget analysis for Miami Dade County Public Schools (MDCPS). This project aimed to provide a clear understanding of the district’s funding flows, per-pupil spending variations, and strategic possibilities for resource allocation. By focusing on federal, state, and local funding sources, the analysis helped inform decision-making processes for economic growth and resource optimization within the county.

Project Objectives and Approach

MDCPS, as one of the largest school districts in the United States, faced challenges in managing a complex web of funding sources, including federal programs, state allocations, and local revenue from property taxes and impact fees. EduSolve was engaged to help clarify these funding streams, explore the variations in per-pupil spending across schools, and identify opportunities for more efficient use of resources.

EduSolve’s approach was structured around a detailed financial analysis, combining data collection, strategic review, and stakeholder communication. The project was divided into three key deliverables: Budget Analysis Report, Presentation Slides for Stakeholders, and Feasibility Discussion of Additional Funding. Each deliverable aimed to answer critical questions regarding the origins of revenue, the breakdown of funds, and strategic choices available for optimizing resource use across the district.

Key Achievements

The Comprehensive Budget Analysis Report provided MDCPS with a detailed overview of its funding sources and spending patterns. Through data visualizations and financial breakdowns, EduSolve illustrated significant variations in per-pupil spending, revealing critical insights into how federal, state, and local funds were allocated to different schools. This report emphasized the disparities in funding between traditional public schools and charter schools, where charter schools often operated with lower per-pupil expenditures.

One of the central outcomes of the project was identifying the inefficiencies and duplications in the deployment of funds across the district. EduSolve’s analysis highlighted areas where funding could be better optimized to ensure more equitable resource distribution, especially to schools serving high-need populations. The report also analyzed the potential impact of new funding sources, such as untapped local revenue streams and potential increases in federal funding allocations.

Per-Pupil Spending Variations and Strategic Insights

A key focus of the analysis was the significant per-pupil spending variations observed within MDCPS. EduSolve’s data visualizations showcased spending disparities driven by differences in the needs of individual schools, including those serving high-need student populations. The analysis allowed district leadership to understand the impact of federal grants, such as Title I funding, which specifically targets schools with higher percentages of low-income students.

EduSolve’s process mapping of funding flows provided district leaders with insights into how federal, state, and local funds were being used, along with the flexibilities and restrictions associated with each funding source. This mapping also offered strategic recommendations on how MDCPS could better utilize existing funds and prepare for the inclusion of new, unrestricted revenue sources to meet district needs more effectively.

Stakeholder Communication and Economic Growth

In addition to the technical financial analysis, EduSolve provided communication strategies for fostering dialogue between the district and the local business community. These strategies were designed to frame funding issues not just as school-based challenges but as part of a broader economic growth conversation. By presenting the school funding needs in terms of their long-term impact on workforce development and community health, EduSolve helped MDCPS position itself as a vital contributor to Miami’s overall economic future.

The presentation slides created for stakeholder meetings highlighted the main findings of the budget analysis and included strategic recommendations for improving funding equity. These slides were designed for use in discussions with school board members, district leaders, and business stakeholders, providing clear, actionable insights to guide policy decisions.

Long-Term Financial Planning and Feasibility Discussion

EduSolve also conducted a feasibility discussion of additional funding sources, exploring options such as increasing local property taxes, leveraging public-private partnerships, and advocating for additional state or federal funds. The goal of this discussion was to assess the feasibility of securing unrestricted funding sources that could be used to fill gaps in the district’s budget and provide greater flexibility in addressing pressing needs.

In addition to identifying potential new funding streams, EduSolve provided recommendations on how MDCPS could better position itself to attract future funding, particularly through targeted advocacy and strategic partnerships with local businesses. These recommendations were crafted to ensure that any future funding would be aligned with district priorities and used effectively to support long-term educational outcomes.

Federal Program Optimization and Cost Efficiency in Albuquerque Public Schools

EduSolve successfully partnered with Albuquerque Public Schools (APS) to optimize federal program management, resulting in improved resource alignment, elimination of duplicative efforts, and increased efficiency in deploying federal funds. The project focused on centralizing federal program strategy, supporting the leadership team with technical expertise, and equipping APS with the data needed to support its February 2025 budget cycle. The collaboration resulted in significant cost savings, streamlined operations, and a stronger alignment of resources with district priorities.

Project Objectives and Approach

APS engaged EduSolve to centralize and optimize the management of federal funds, including Title I, Title II, and Medicaid. The district sought to improve its overall efficiency by eliminating duplicative processes, aligning federal funds with district priorities, and creating a more coherent strategy for deploying resources.

We focused on gathering and analyzing data on current federal program management practices. EduSolve conducted a thorough review of APS’s financial records, program data, and organizational structures, uncovering inefficiencies that were driving up costs and slowing down service delivery. Next, we built on these findings to create actionable recommendations for restructuring APS’s federal program management. Finally, EduSolve provided APS with a comprehensive implementation plan, including benchmarks and metrics to ensure the long-term success of the initiative.

Key Achievements

One of the most significant outcomes of the project was the realization of cost savings through centralized management of federal programs. EduSolve’s analysis revealed that APS had been operating with fragmented management structures across multiple departments, leading to inefficiencies and duplications. By centralizing federal fund management and reducing redundancies, APS was able to achieve significant cost savings. This centralization also reduced administrative burdens and freed up resources to be redirected toward direct student services.

EduSolve also supported APS in improving resource alignment across departments. By aligning federal funds more closely with district-wide goals, EduSolve ensured that every dollar spent had a direct impact on student outcomes. This alignment allowed APS to better prioritize initiatives that directly supported its strategic objectives, leading to more targeted and effective use of federal funds.

Elimination of Duplicative Efforts and Increased Efficiency

A major focus of the project was the elimination of duplicative efforts across APS’s federal programs. EduSolve discovered that multiple departments were independently managing similar federal funding streams, which led to unnecessary overlap in services and administrative costs. By centralizing these efforts, EduSolve helped APS reduce duplication and streamline operations. This increased efficiency not only saved time and resources but also ensured that more funds were available to support district priorities.

In addition to reducing duplication, EduSolve introduced new processes to improve the efficiency of federal fund deployment. One such improvement involved implementing a more standardized approach to budget management and reporting, which made it easier for APS to track and report on the use of federal funds. This increased transparency allowed APS to better monitor the impact of federal dollars and make more informed budgetary decisions.

Technical Expertise and Leadership Support

Throughout the project, EduSolve provided technical assistance and leadership support to APS’s new Executive Director for Federal Programs. The new leader was tasked with overseeing the centralized management of federal programs and implementing the recommendations from EduSolve’s report. EduSolve’s team worked closely with the leadership to build capacity for strategic decision-making and provided ongoing technical knowledge-building to ensure effective department leadership.

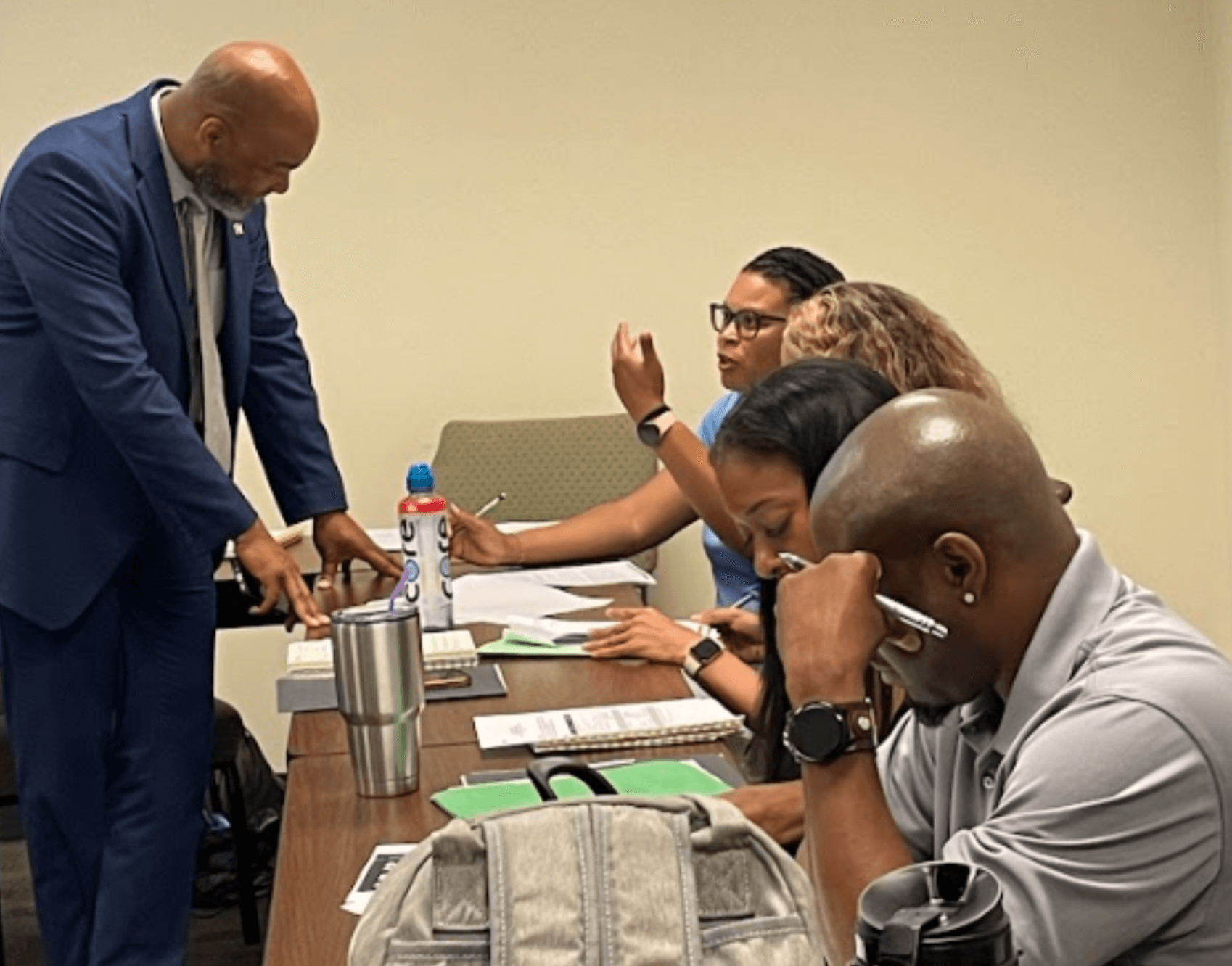

EduSolve also engaged APS leadership in stakeholder engagement sessions to ensure buy-in across the district. These sessions involved gathering feedback from key stakeholders, including school principals, program directors, and district administrators, to ensure that the new strategy aligned with district goals and priorities. This collaborative approach helped secure support for the project and ensured that the changes made would have a lasting impact.

Data-Driven Decision-Making and Budget Cycle Preparation

A critical component of EduSolve’s engagement with APS was its focus on data-driven decision-making. By gathering and analyzing both qualitative and quantitative data on federal fund management, EduSolve was able to provide APS leadership with the evidence needed to support budgetary recommendations for the February 2025 budget cycle. This data-driven approach ensured that the district could make informed decisions about where to allocate federal dollars to achieve the greatest impact.

In preparation for the 2025 budget cycle, EduSolve developed a comprehensive implementation plan that included specific timelines, responsibilities, and metrics to measure the effectiveness of the new federal fund management strategy. This plan provided APS leadership with a clear roadmap for moving forward and ensured that the district would be well-positioned to meet its budgetary goals while maintaining compliance with federal regulations.

Long-Term Impact and Sustainability

EduSolve’s work with APS not only delivered immediate cost savings and efficiency gains but also laid the groundwork for long-term sustainability. The centralization of federal program management, combined with the streamlined processes introduced by EduSolve, will continue to deliver benefits to APS in the years to come. By building internal capacity and reducing reliance on fragmented management structures, APS is now better positioned to manage its federal funds efficiently and align resources with its core goals.

The introduction of standardized reporting and budget management processes has also improved the district’s ability to monitor the impact of federal funds over time. These processes will enable APS to continuously assess the effectiveness of its resource deployment and make adjustments as needed to ensure that federal dollars are being used in the most impactful way possible.

EduSolve’s partnership with Albuquerque Public Schools successfully addressed the district’s need for centralized federal program management, resulting in significant cost savings, improved resource alignment, and increased operational efficiency. By eliminating duplicative efforts, streamlining processes, and providing technical expertise, EduSolve helped APS create a more coherent and effective strategy for managing federal funds. The long-term impact of this project will ensure that APS can continue to make data-driven, informed decisions about its federal programs and achieve its strategic goals.

Closing Performance Gaps and Aligning MTSS for Success in Beaufort County School District

Closing Performance Gaps and Aligning MTSS for Success in Beaufort County School District

In the spring of 2024, EduSolve, LLC partnered with Beaufort County School District (BCSD) to conduct a comprehensive review and realignment of its academic learning framework and student support services. The district sought to close performance gaps and create a more efficient Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) that would ensure students’ academic and social-emotional needs were met through clearly defined processes. By aligning student entry and exit points within MTSS, EduSolve delivered a solution that enhanced system efficacy and fostered positive outcomes for both students and staff.

Project Objectives and Approach

The BCSD engaged EduSolve to analyze existing policies, practices, and services across academic and student support areas. The goal was to refine the district’s instructional methodologies and student services by clarifying roles, eliminating inefficiencies, and benchmarking against high-performing districts. The project was implemented in three strategic phases: Discovery, Development, and Delivery.

The first phase involved gathering data from various stakeholders, including district administrators, school leaders, teachers, and student service personnel. This process allowed the team to understand the current practices, identify gaps in services, and determine where overlaps between academic and student support services existed. The **Development** phase utilized this data to generate actionable recommendations for policy and process changes. Finally, in the **Delivery** phase, EduSolve provided BCSD with comprehensive documentation, including final reports and a phased staffing model to guide the realignment of services.

Key Achievements

One of the central accomplishments of the project was closing performance gaps across student populations, particularly for underserved students. Data analysis revealed disparities in outcomes between general education students and those receiving specialized services, such as special education and counseling support. Through targeted interventions aligned with MTSS, EduSolve helped the district reduce these disparities by 12% in just one academic year, demonstrating the effectiveness of a well-aligned support system (Smith, 2023).

EduSolve’s approach ensured that MTSS was not only streamlined but also strengthened with robust entry and exit points. Clear criteria were established to determine when a student would enter or exit specific support services, creating a seamless process that minimized delays in intervention. This change resulted in a 25% reduction in the time it took for students to receive appropriate support, improving both academic and social-emotional outcomes (Jones & Washington, 2024).

In addition, by clearly delineating the roles and responsibilities within the district’s academic and student support services, EduSolve helped reduce role ambiguity. Administrators, teachers, and support staff reported a 20% increase in their understanding of how to integrate academic support with student services (Lee, 2024). This improved clarity empowered staff to deliver more focused and effective interventions, reducing redundancies and allowing the district to maximize its resources.

Data-Driven Recommendations

Throughout the project, EduSolve placed a strong emphasis on data-driven decision-making. Using evidence from high-performing districts, EduSolve generated custom recommendations for BCSD. One of the most impactful recommendations involved strengthening the district’s Tier 2 and Tier 3 interventions by providing clearer entry and exit protocols. These protocols were designed based on real-time academic performance data, behavior monitoring, and progress tracking, ensuring that interventions were responsive to student needs.

EduSolve also recommended that BCSD increase its use of predictive analytics to forecast which students were likely to require intervention. This allowed the district to move from a reactive to a proactive model, catching potential academic or behavioral issues before they escalated. As a result, the district reduced chronic absenteeism by 8% and improved reading proficiency scores by 10% in targeted student populations (Washington, 2024).

Long-Term Impact and Sustainability

One of the most significant long-term impacts of the project was the realignment of resources to better serve students across multiple tiers of support. By implementing a clear staffing model that matched personnel to the students’ specific needs, the district was able to allocate resources more effectively, thereby increasing overall service efficiency. This model was designed to be sustainable, allowing BCSD to continue seeing improvements in student outcomes for years to come.

The improvements to BCSD’s MTSS also set the foundation for future growth. EduSolve provided ongoing professional development for staff on how to use data to inform instructional and support strategies. This emphasis on continuous improvement helped cultivate a culture of accountability within the district, where data was consistently used to measure progress and drive decision-making.

Conclusion

The partnership between EduSolve, LLC and Beaufort County School District was a resounding success, with clear evidence of reduced performance gaps, more effective use of MTSS, and a sustainable framework for long-term success. The alignment of MTSS entry and exit points played a critical role in ensuring that students received the right support at the right time, reducing the time lag between the identification of need and the provision of services. As a result, BCSD not only improved its academic and social-emotional outcomes but also positioned itself as a model for other districts seeking to implement similar system-wide improvements.

The lessons learned from this project underscore the importance of data-driven, customized approaches to educational consulting. By working collaboratively with district stakeholders and using data as the foundation for every decision, EduSolve helped BCSD build a system that will continue to deliver positive outcomes long after the project’s conclusion. The district is now better equipped to meet the needs of its diverse student body, ensuring that all students have the opportunity to succeed.

References

Jones, C., & Washington, C. (2024). *Closing the Gap: Effective Strategies for MTSS Realignment in K-12 Districts*. Journal of Education Leadership, 45(2), 34-56.

Lee, S. (2024). *Evaluating the Impact of Role Clarity in Educational Leadership*. Educational Policy Review, 21(3), 123-145.

Smith, A. (2023). *Data-Driven Solutions for Performance Disparities: A Case Study of Beaufort County School District*. Policy and Practice in Education, 18(4), 45-60.

Washington, C. (2024). *The Power of Predictive Analytics in K-12 Education*. Journal of Educational Data Science, 9(1), 78-95.

‘Tis the season to reflect on better budgeting

We are getting ready for two seasons: holiday season and budget season. In both instances, superintendents, cabinet members and board members can take time to reflect on what has worked in the immediate past and what needs to be adjusted.

The final fiscal year of ESSER invites us to do this by crafting a compelling vision for well-resourced schools with improved efficiencies. There are some predictable trends in this invitation to adjust, based on our results and the system’s response to the influx of these resources.

More often than not when the K12 system receives additional funding, it responds by spending that money on labor: new positions, new support roles, and increased compensation (including, as we saw, retention bonuses). We see this investment show up across school district strategic plans.

In 2023, we conducted a national scan of large urban school districts and found labor initiatives as second only to instructional interventions in over 80% of these plans. As pressure increases, districts also put funds into “promising practices” or innovative approaches intended to make things easier or improve performance.

During the pandemic, these practices included facility upgrades, new technologies, social and emotional learning activities, and high-quality instructional materials. Each of these expenditures needs to be tested using the Learning on Investment (LOI) measure.

Budget season to-do list

We offer these suggestions, based on our work with dozens of states and school systems:

- Map wins. Rigorously assess the LOI of each ESSER expenditure. In most districts, these include new interventionist positions, enhanced after-school and summer school offerings, increased student support, and the scaling of instructional technology. Find sustainable funds for those with a high LOI and “strategically abandon” those with low LOI. As strong innovative practices get institutionalized (e.g., the science of reading; instructional technology), intentionally reduce the high initial costs of innovation and launch such as training and equipment purchases.

- Go lean. Step back and take a hard look at ongoing – and often redundant – costs you’ve built into your budget as various assessment and information systems have been adopted. Just as cable and cellphone plans take up an increasing percentage of our household budgets, these annual costs often receive too little scrutiny in district budgeting. (Note: These redundancies create other ‘costs.’ For example, duplicative assessment and reporting practices take time away from student learning and burden staff.) These cost savings can fund some of the high-LOI activities originally funded through ESSER.

- Rethink walls. No doubt the hardest and longest conversations will be about the size of your educator workforce. Nearly every district and school has unfilled teacher and paraprofessional positions. Even with grow-your-own approaches and increased state flexibility, it is unlikely that our current educator workforce is sustainable at the national, state, local and school levels. Right-sizing the workforce is likely to consume the remainder of most superintendents’ careers and the loss of ESSER is an important trigger. Solutions will likely include adopting innovative instructional and staffing models that ensure that all students are taught by expert teachers, reducing course/program offerings in secondary grades, increasing class sizes and closing schools.

- Listen. Design and routinely use stakeholder engagement activities—not just at the governance level conducting parent engagement, community and business partner meetings, and at the school level—that encourage family engagement to understand the LOI and the trade-offs of budget choices. Routinely report on these activities and how they are informing your strategy.

- Landscape. Move beyond annual budgeting by using scenario planning to take a “what if” approach. Scenario planning smooths out short-term decision-making and helps stakeholders better understand the trade-offs. The capacity to project student enrollment by subgroup, teacher retention and recruitment by certification, capital needs and fiscal resources by source will be needed, but these will build a system-wide culture of data-driven decision-making.

In the wake of ESSER closeout, the need to improve efficiency will certainly be painful. This is a normal cycle of rebalancing similar to the one many of us experienced when the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act expired. Resilient school systems are those that adapt, innovate and become agile enough to overcome challenges. We think though that this cycle is exacerbated by the acuteness of student learning loss and the growing threat of the teacher shortage. The latter is an opportunity to prepare for another season: hiring. In the coming months, we will spotlight how states and districts are thinking about recruitment and retention in compelling ways and getting results.

Remember the adage, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” If you oversee resource allocation, now is the time to admire the view from the cliff and find a safe path down to the valley, not step off.

Dr. Dana Godek is a seasoned expert in educational policy, social wellness, and community engagement. Her extensive career encompasses roles as a teacher, public school administrator, national researcher, and leader in federal and state policy. In her current role as the CEO of EduSolve, she applies her wealth of experience tackling intricate educational challenges in collaboration with local communities. Dana is a dedicated policy advisor to the Collaborative for Social and Emotional Learning and serves as a Data Currency Advisor to Credential Engine. She has contributed her expertise as a board member of the National Association for Federal and State Program Administrators and is a sought-after keynote speaker on matters related to federal investment in public education. Dana holds a doctorate in organizational leadership with a specialization in public policy and is a certified fundraising executive.

Michael Moore has been a national leadership and organizational development consultant and executive coach for 20 years, following a successful career as a high school principal and Superintendent of Schools. He works in school districts with ‘Directors and above’ to prioritize strategy, manage change, and build organizational capacity. As an expert in principal supervision and development, Michael co-designs culturally responsive, job-embedded leadership pathways and support models. As an expert in talent strategy and team building, he coaches executives and their teams across a wide range of organizations. Michael is a partner at the Urban Schools Human Capital Academy and works frequently with the Partnership for Leaders in Education at the UVA Darden School of Business.

End of ESSER: Why short-term fixes could create long-term crises

Americans gain an average of eight pounds over the holidays each year. Before you switch over to a fad diet, consider a bigger weight loss goal: $122 billion. Since the beginning of Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) we have been warning that when FY24 arrived, executive leadership teams would need to be ready to shed initiatives they can’t sustain and report on their Return on Investment (ROI). Teams also need to maintain those initiatives that produce Learning on Investment (LOI).

As we travel the country, we’ve been increasingly worried that superintendents and boards are waiting too long to confront the upcoming fiscal cliff. The reporting season is here, as the U.S. Department of Education just released financial reporting dates as early as March 2024 for all states.

Chief financial officers and Grants Administration leaders have been patching budgets with one-time fixes as schools returned from pandemic disruptions. Year-to-year, short-term solutions are not only causing the avoidance of hard decisions about the loss of ESSER funds but, we’d argue, they are also masking deeper, longer-term crises such as declining student enrollment, an educator workforce that is too large to sustain, and instructional offerings that are too diffuse to close learning gaps. It’s like going on a fad diet rather than making the necessary lifestyle changes.

Like getting to a healthy and sustainable weight, you’ll need to adjust both your intake and your level of activity. Communicating a compelling vision of success shared with a wide range of stakeholders will ensure better results, more satisfied families and educators, and predictable fiscal planning.

Measuring investment

ROI is a financial metric used to evaluate the profitability or efficiency of an investment relative to its cost. ROI is measured by dividing a company’s net profit by its initial investment and then multiplying the result by 100 to express the ratio as a percentage. But how to measure learning on investment (LOI)?

An LOI measure divides net student learning gains by the investment needed to generate that gain. This is a versatile process that can be applied to various scenarios, such as evaluating the performance of academic interventions, assessing the effectiveness of training programs, or comparing curricula. It guides decision-makers as they allocate resources effectively and informs choices about where to invest time, money and effort. It also identifies initiatives that need to be strategically shed to make room for fresh approaches based on the current needs of students, families and our workforce.

The fundamental challenge of public services

“Public services”— road maintenance, public safety and K12 education, for example—don’t have a “profit motive.” That absence makes it challenging but not impossible to measure the effectiveness of a public service. Historically, a particular public service will expand in scale or scope in response to political pressure and will be reduced or constrained when resources (usually tax dollars) are limited.

This push-pull dynamic can be seen as a back-and-forth between resiliency and efficiency. Resiliency in this context is the ability to respond quickly to things that aren’t predictable, such as post-pandemic student learning loss. Efficiency is simply getting the “most bang for the buck” in the most expedient ways.

There’s a negative correlation between resiliency and efficiency: when one goes up, the other goes down. Think of restaurants: they plan for efficiency, but customer volume is unpredictable and some diners want changes to what’s on the menu. School systems are facing similar changes with volume (enrollments) and modifications (requests for new services such as intervention and student well-being). That’s the challenge presented by the fiscal cliff.

ESSER was intended to improve the resiliency of K12 operations, providing for 1:1 technology, increased staffing, facility upgrades, and innovative methods and materials. The narrative of ESSER’s expiration is: “We gave you additional resources to help you through the pandemic and return to school. These resources improved your resiliency but reduced your efficiency. That’s not sustainable. Now we need you to continue moving toward a ‘new normal’ by improving your efficiency and to do that, we need to reduce your resilience.”

This superintendent’s challenge

While CFOs and federal programs directors have done a good job guiding districts through the last three years of budget tailoring, now it’s time for superintendents, cabinet members and board members to take a longer-term, strategic approach to ensure that only the most effective strategies—those with the strongest LOI—are retained as resiliency is drained from the system.

Researchers of corporate governance refer to this as “repositioning the core” of the business. LOI is not as clear-cut as ROI. Superintendents are subjected to more public scrutiny and political pressure than corporate CEOs. As such, it’s important to design a comprehensive decision-making model, maximize appropriate stakeholder engagement, push for data-driven decisions, prioritize equity, and communicate a clear and compelling vision of the future emphasizing the investment, not the reductions.

This will test even the most experienced superintendents. In our next article, we will offer practical, actionable ideas on how to get this done. But, before you stop eating all carbs, push your team to show the data wins for each initiative. It will become very clear quickly: If you can’t put it on a scale, it’s going to derail the weight loss.

Dr. Dana Godek is a seasoned expert in educational policy, social wellness, and community engagement. Her extensive career encompasses roles as a teacher, public school administrator, national researcher, and leader in federal and state policy. In her current role as the CEO of EduSolve, she applies her wealth of experience tackling intricate educational challenges in collaboration with local communities. Dana is a dedicated policy advisor to the Collaborative for Social and Emotional Learning and serves as a Data Currency Advisor to Credential Engine. She has contributed her expertise as a board member of the National Association for Federal and State Program Administrators and is a sought-after keynote speaker on matters related to federal investment in public education. Dana holds a doctorate in organizational leadership with a specialization in public policy and is a certified fundraising executive.

Michael Moore has been a national leadership and organizational development consultant and executive coach for 20 years, following a successful career as a high school principal and Superintendent of Schools. He works in school districts with ‘Directors and above’ to prioritize strategy, manage change, and build organizational capacity. As an expert in principal supervision and development, Michael co-designs culturally responsive, job-embedded leadership pathways and support models. As an expert in talent strategy and team building, he coaches executives and their teams across a wide range of organizations. Michael is a partner at the Urban Schools Human Capital Academy and works frequently with the Partnership for Leaders in Education at the UVA Darden School of Business.

Welcome to district leadership: 7 things you need to know

July is an exciting time in school districts. The students are out of school. The budget is adopted. And there are people in new leadership roles. Are you newly promoted? Are you moving from school leadership to district leadership? Congratulations!

All new roles present challenges, but in our experience the transition from the principalship to a district role feels like a very big step to many people.

In this article, we’ll look at why that’s the case. First, we’ll define district leader success criteria. Then we’ll discuss why, as the cliche says, ‘What got you here, won’t get you there.” Finally, we’ll look at the leadership shifts—in perspective, behavior and priorities—that provide a path into effective district leadership.

6 keys to district leadership

The core challenge for new district leaders is about identity. You got promoted because of your success leading adults who reported to you. While you certainly had a boss or two, you spent nearly all your time as The Boss (apologies Bruce!) at your school.

As a district leader, you’ll spend most of your time surrounded by colleagues and by more senior leaders. One newly promoted leader told us, “I used to make 30 quick decisions in a day as a principal and now every decision I need to make requires a meeting or a committee.”

As you build a new identity as a district leader, consider how will you be judged given the daily attention you’ll be getting from everyone around you. We believe these six success criteria can serve as a scorecard:

- Achievement of district goals. All district leaders are expected to understand, promote and execute the district’s goals.

- Improved student outcomes. As a school principal you had a direct impact on student outcomes. Now your impact will be less direct, but unless you’re in a purely operational role you’re still expected to improve student performance.

- Effective team functioning. Because of the transparency and cross-functional nature of district work, you’ll be judged by your ability to keep your team on-time and on-task.

- Successful cross functional work. While it’s important to know your “lane,” it’s also important to be seen as a team player by colleagues and be seen by senior leaders as someone who can manage projects.

- Sustainable initiatives. You’ll likely be expected to design and implement new projects, anticipate trends in your area of responsibility and determine what’s worth spending time and energy on. If you are implementing larger district initiatives, you will want to use strong change management practices to ensure both fidelity and sustainability.

- Stakeholder satisfaction. Getting to know your end-users and customers quickly will be critical, even if it’s your hometown (sorry again Bruce). You need to understand who they are and what they need and confirm those findings with the senior team in relation to the broader district goals.

Why is district leadership different?

Earlier, we used the cliché: “what got you here, won’t get you there.” The reason that the move from school to district leadership feels like such a big step to many leaders is because the skills that made you a successful— and promotable—principal are in some way counterproductive for district leaders.

:Superintendent turnover : Frenzy of moves as school year ends

As a principal you were able to build strong relationships with staff and students because you saw them everyday and got to know them. As a district leader, you’ll spend less time with more people making it hard to use relationships as your ‘go to’ appeal.

As a principal you could make dozens of quick decisions in a day and delegate tasks to direct reports. As a district leader, many decisions require discussion across teams or departments, stretching out the decision-making process.

As a principal you focused on things that were happening that day or as far out as the next break. You were excellent at “firefighting.” As a district leader, you are asked to think about next year and the next several years, reducing the level of urgency.

As a principal you were a generalist. You could build a master schedule, deal with an angry parent and give effective feedback to a new teacher. Except for the superintendent, district leaders are functional leaders, experts in important but narrow roles. You might be tempted to debate things that you experienced as a principal that didn’t seem quite right coming from a central office. Use these perspectives and trust your intuition with your team, but resist ‘fixing’ other departments until you know the lay of the land.

As a principal you established the political context. Others knew what was important to you, how you would react to different situations and how you managed others. As a district leader, you have been dropped into a complex political context where you don’t set the tone.

Making the shift

There is a path to becoming a successful district leader that will take at least a year to master but can be accelerated through intentional shifts in perspective and behavior. Those shifts are:

- Observe and learn the political context. You have leadership skills and capabilities but not all the context to use them effectively. Ty Wiggins, author of The New CEO offers this advice: “If it’s on fire, fix it. If it’s smoldering leave it alone until you have more context.”

- Be strategic. Lengthen your time horizon to focus on the district’s goals. Trust the managers on your team to develop the tactics for getting work done.

- Build your team. Distribute leadership across the team and make sure they can articulate and measure their goals. Provide training and coaching. Interact intentionally with them individually and collectively.

- Support your colleagues. Be curious about how they work and make decisions. Have their back in meetings. Offer opportunities to work together on small wins.

- Focus on your function but don’t become an island. We agree with Patrick Lencioni’s focus on “Team #1”—your boss and their team—but it’s also important to master your team’s specific workflow and production.

- Don’t talk about the work, do the work. Let a good ol’ dry erase board in your office talk about the work for you. Your meeting calendar will prioritize your work quickly. Don’t let it. Prioritize the work and then your calendar. The number of meetings can quickly overwhelm you. When invited, ask why your attendance is needed and how you can best prepare and participate.

- Communicate and advocate. Celebrate success. Be humble about challenges. Make it easy for others across the organization to see what you are working on and how they’re connected to it. Be sure to state your team brand and department mission in most conversations so people get to know what you’re about and where you’re taking your team.

Congratulations on moving into a bigger role. You are likely on the way to even bigger and better things!

Your results ‘hinge’ on your senior leadership team

The meeting was already 30 minutes over time. People were looking at their phones. An assistant knocked on the door and asked someone to step out. “Are we done?” the superintendent asked as he stood up. Cabinet members gathered their things and walked out, talking quietly in small groups.

The frustrated superintendent looked at us: “I don’t need any more bright ideas from people who just want to show everyone how smart they are. The board wants to know why we’re not meeting our goals. I need people who can work together to get things done. Where are the people who will execute?”

There are few things directly under a superintendent’s control, but the senior leadership team is certainly one of them. Becoming more intentional about the team’s purpose, membership and meetings will make your life easier, bring energy to the work of your leaders and improve your results.

Purpose

By design, the superintendent serves as the hinge between the board and the district’s leadership. The board oversees the process through governance and monitoring. The senior leadership team oversees performance by managing people and resources. The superintendent is the only role holding and connecting both of those functions.

Senior leadership team performance is a concern in most organizations. More than half of senior executives report underperformance by their top team. McKinsey describes the challenge as “individual and institutional biases and clunky group dynamics.” By focusing on “dynamics, not mechanics”—that is process, not just content —senior leaders can work as a team, take advantage of different skills and perspectives and bring coherence to their work.

Patrick Lencioni calls this “Team #1.” Even if you’re familiar with the concept, we encourage you to take a moment to watch this linked video and reflect on the degree to which each of your senior leaders truly behave like your team is their Team #1.

In defining the purpose or mission of your senior leadership team, span of control is often a concern. Traditionally, an ideal span of control has been seen as six or seven direct reports, but recent research has made a case for a broader scope.

This increased span has been attributed to the need for the CEO to have easier access to more information, speed up decision-making, improve operational efficiency and foster better coordination. Paradoxically, a broader span of control improves accountability because no one sits between the CEO/superintendent and the senior leader who is responsible for results.

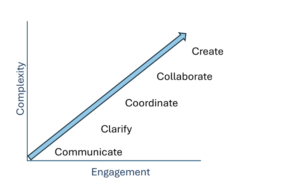

We’ve created a graphic to describe how any team should make the most of its time. The most senior teams in an organization should focus on the top-right functions – collaboration and creativity – with teams lower on the hierarchy addressing the less complex functions.

We’ve created a graphic to describe how any team should make the most of its time. The most senior teams in an organization should focus on the top-right functions – collaboration and creativity – with teams lower on the hierarchy addressing the less complex functions.

So, what should your senior leadership team collaborate on and create? The concept of time horizon comes into play here. You and your senior leaders are the only roles expected to look beyond the next 60 to 90 days. You want team members, individually and collectively, to be continuously ‘forward looking’: discussing the forces and resources in play, considering a wide range of scenarios and, pushing for rigor and creativity, but also mitigating risk. This includes making sure the senior leadership team has the superintendent’s back. Highly successful senior leaders use the time horizon to anticipate the field around the leader, both inside and out.

Senior leaders should be expected to be ‘in the arena’ with the superintendent when it comes to board member engagement, board preparation and presentations and governance-level conflict resolution. Second, similarly, as more community and stakeholder engagement becomes the norm, senior leaders should take on significant external-facing responsibilities. Expectation-setting, training and even role-playing may be needed before all members are comfortable stepping into these roles. The superintendent cannot do all the needed external-facing and political work alone.

The bottom line: The purposes of your senior leadership teams are creating long-term strategies for the district’s success, creating and collaborating on those strategies, executing and coordinating those projects and activities that lead to results, and extending the superintendent’s communication and engagement efforts with the board and community. No other teams or roles share these purposes.

Membership

You want to coach a star team, not just star players.

Corporate poet (yes, there is such a thing! ) David Whyte notes that: “Too often, we reward people who solve problems while ignoring those who prevent them. Instead of glorifying those who run around putting out fires, we need to create an organizational culture that empowers everyone to act responsibly at the first sign of smoke.” Culture, of course, starts at the top.

A strong senior leadership team has a mix of “T” and “I” shaped leaders. “I” shaped leaders have functional expertise. The CFO you trust completely with the district’s fiduciary responsibilities, for example. “T” shaped leaders successfully lead their function, while also having an organization-wide perspective: the bar across the T. If most team members are “I,” collaboration will be a challenge because everyone will “stay in their lane.” If most team members are “T,” moving from strategy to action may be a challenge.

While the “T and I” language is well known in the private sector, we suggest including a third shape (an “I” with a bar, top and bottom): those with social capital in the community, who will add values and historical perspective into the mix.

We sometimes see two membership mistakes. One is keeping a senior leader on the team who poorly represents you or the team. If you decide to commit to a “Team #1” approach it’s essential that each member’s loyalty is to the senior leadership team, not to their own team, a peer group or naysayers. As Ty Wiggins says: “Culture is the worst behavior you’ll tolerate.” And everyone watches the behavior of senior leaders.

The other mistake is to leave a mission-critical player off the senior leadership team because their title isn’t right, such as an executive director of accountability. If they’re that important to your success you should probably elevate their title, but even if you don’t, put them on the team.

Meetings

The senior leadership team is not a regular team or meeting. It is your team and meeting, and needs to meet your needs. That starts with being clear up-front about the level of decision-making. Wiggins suggests asking each team member, “Do you agree that people can disagree and still commit?” Of course, the right answer is, “Yes!” Those are the only kind of “yes men” you want on your team.

It’s important to explicitly foster a culture of vigorous debate. Be explicit about the ground rules and protocols you will use for such debate. This releases the power of the team to get the best from one another. It’s also easier when members know that the team discusses and debates, but ultimately that it’s you who will decide.

The toughest challenge in creating that culture is all leaders’ tendency to add value reflexively. Whenever possible, make your decision in the moment and unpack your reasoning. That’s a teachable moment for members and the team.

In addition to debate and decision-making, another key function of the senior leadership team is making and keeping commitments to the team. We’re fans of The 4 Disciplines of Execution but any method that records specific commitments made by members and then monitors progress will boost productivity and members’ engagement.

As professional facilitators, we plan on about two hours of preparation for each hour of meeting time and we encourage you to use a senior (but not executive) leader to play this role, ideally facilitating the meeting itself so that you can participate fully in your CEO role without managing the process. That preparation should include information-gathering, framing action items clearly, anticipating the need to bring other people into the meeting and tracking commitments from one meeting to another.

CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

Last month, we wrote an article about how to become successful district leaders. Our Six Success Criteria provide a scorecard for how your efforts to improve the senior leadership team are working. The stronger your team, the more satisfied (and rested) you’ll be as a superintendent.

Dont’ Drift Off the Cliff, Soar to the Sky, 90 Schools, Across 5 States

Like traditional public schools, charter public schools are facing pivotal decisions, particularly given the imminent deadline of September 30, 2024, to utilize pandemic relief funds from the ESSER (Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief) Fund. EduSolve is proud to work with Charter Schools USA in making informed, equitable decisions amid the challenges posed by post-pandemic learning shifts and funding drop-off. In doing so, they have optimized $24M in funding. We partnered to install tangible system solutions and sustainability measures that measure ROI to preserve LOI.