The meeting was already 30 minutes over time. People were looking at their phones. An assistant knocked on the door and asked someone to step out. “Are we done?” the superintendent asked as he stood up. Cabinet members gathered their things and walked out, talking quietly in small groups.

The frustrated superintendent looked at us: “I don’t need any more bright ideas from people who just want to show everyone how smart they are. The board wants to know why we’re not meeting our goals. I need people who can work together to get things done. Where are the people who will execute?”

There are few things directly under a superintendent’s control, but the senior leadership team is certainly one of them. Becoming more intentional about the team’s purpose, membership and meetings will make your life easier, bring energy to the work of your leaders and improve your results.

Contents

Purpose

By design, the superintendent serves as the hinge between the board and the district’s leadership. The board oversees the process through governance and monitoring. The senior leadership team oversees performance by managing people and resources. The superintendent is the only role holding and connecting both of those functions.

Senior leadership team performance is a concern in most organizations. More than half of senior executives report underperformance by their top team. McKinsey describes the challenge as “individual and institutional biases and clunky group dynamics.” By focusing on “dynamics, not mechanics”—that is process, not just content —senior leaders can work as a team, take advantage of different skills and perspectives and bring coherence to their work.

Patrick Lencioni calls this “Team #1.” Even if you’re familiar with the concept, we encourage you to take a moment to watch this linked video and reflect on the degree to which each of your senior leaders truly behave like your team is their Team #1.

In defining the purpose or mission of your senior leadership team, span of control is often a concern. Traditionally, an ideal span of control has been seen as six or seven direct reports, but recent research has made a case for a broader scope.

This increased span has been attributed to the need for the CEO to have easier access to more information, speed up decision-making, improve operational efficiency and foster better coordination. Paradoxically, a broader span of control improves accountability because no one sits between the CEO/superintendent and the senior leader who is responsible for results.

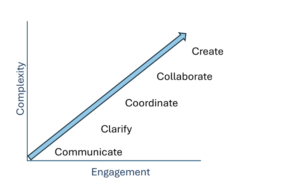

We’ve created a graphic to describe how any team should make the most of its time. The most senior teams in an organization should focus on the top-right functions – collaboration and creativity – with teams lower on the hierarchy addressing the less complex functions.

We’ve created a graphic to describe how any team should make the most of its time. The most senior teams in an organization should focus on the top-right functions – collaboration and creativity – with teams lower on the hierarchy addressing the less complex functions.

So, what should your senior leadership team collaborate on and create? The concept of time horizon comes into play here. You and your senior leaders are the only roles expected to look beyond the next 60 to 90 days. You want team members, individually and collectively, to be continuously ‘forward looking’: discussing the forces and resources in play, considering a wide range of scenarios and, pushing for rigor and creativity, but also mitigating risk. This includes making sure the senior leadership team has the superintendent’s back. Highly successful senior leaders use the time horizon to anticipate the field around the leader, both inside and out.

Senior leaders should be expected to be ‘in the arena’ with the superintendent when it comes to board member engagement, board preparation and presentations and governance-level conflict resolution. Second, similarly, as more community and stakeholder engagement becomes the norm, senior leaders should take on significant external-facing responsibilities. Expectation-setting, training and even role-playing may be needed before all members are comfortable stepping into these roles. The superintendent cannot do all the needed external-facing and political work alone.

The bottom line: The purposes of your senior leadership teams are creating long-term strategies for the district’s success, creating and collaborating on those strategies, executing and coordinating those projects and activities that lead to results, and extending the superintendent’s communication and engagement efforts with the board and community. No other teams or roles share these purposes.

Membership

You want to coach a star team, not just star players.

Corporate poet (yes, there is such a thing! ) David Whyte notes that: “Too often, we reward people who solve problems while ignoring those who prevent them. Instead of glorifying those who run around putting out fires, we need to create an organizational culture that empowers everyone to act responsibly at the first sign of smoke.” Culture, of course, starts at the top.

A strong senior leadership team has a mix of “T” and “I” shaped leaders. “I” shaped leaders have functional expertise. The CFO you trust completely with the district’s fiduciary responsibilities, for example. “T” shaped leaders successfully lead their function, while also having an organization-wide perspective: the bar across the T. If most team members are “I,” collaboration will be a challenge because everyone will “stay in their lane.” If most team members are “T,” moving from strategy to action may be a challenge.

While the “T and I” language is well known in the private sector, we suggest including a third shape (an “I” with a bar, top and bottom): those with social capital in the community, who will add values and historical perspective into the mix.

We sometimes see two membership mistakes. One is keeping a senior leader on the team who poorly represents you or the team. If you decide to commit to a “Team #1” approach it’s essential that each member’s loyalty is to the senior leadership team, not to their own team, a peer group or naysayers. As Ty Wiggins says: “Culture is the worst behavior you’ll tolerate.” And everyone watches the behavior of senior leaders.

The other mistake is to leave a mission-critical player off the senior leadership team because their title isn’t right, such as an executive director of accountability. If they’re that important to your success you should probably elevate their title, but even if you don’t, put them on the team.

Meetings

The senior leadership team is not a regular team or meeting. It is your team and meeting, and needs to meet your needs. That starts with being clear up-front about the level of decision-making. Wiggins suggests asking each team member, “Do you agree that people can disagree and still commit?” Of course, the right answer is, “Yes!” Those are the only kind of “yes men” you want on your team.

It’s important to explicitly foster a culture of vigorous debate. Be explicit about the ground rules and protocols you will use for such debate. This releases the power of the team to get the best from one another. It’s also easier when members know that the team discusses and debates, but ultimately that it’s you who will decide.

The toughest challenge in creating that culture is all leaders’ tendency to add value reflexively. Whenever possible, make your decision in the moment and unpack your reasoning. That’s a teachable moment for members and the team.

In addition to debate and decision-making, another key function of the senior leadership team is making and keeping commitments to the team. We’re fans of The 4 Disciplines of Execution but any method that records specific commitments made by members and then monitors progress will boost productivity and members’ engagement.

As professional facilitators, we plan on about two hours of preparation for each hour of meeting time and we encourage you to use a senior (but not executive) leader to play this role, ideally facilitating the meeting itself so that you can participate fully in your CEO role without managing the process. That preparation should include information-gathering, framing action items clearly, anticipating the need to bring other people into the meeting and tracking commitments from one meeting to another.

CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

Last month, we wrote an article about how to become successful district leaders. Our Six Success Criteria provide a scorecard for how your efforts to improve the senior leadership team are working. The stronger your team, the more satisfied (and rested) you’ll be as a superintendent.